Tragic Details About Saturday Night Live Original Cast Member Gilda Radner

This article includes mentions of disordered eating.

With 2025 marking the 50th anniversary of "Saturday Night Live," a sense of nostalgia is permeating the late-night sketch comedy show that first appeared on television screens in 1975. Along with a variety of TV specials and the acclaimed film "Saturday Night" (about the chaotic 90 minutes leading up to the very first show), the focus is returning to the show's original cast.

Dubbed the "Not Ready for Prime Time Players," this assemblage of upstart young comedians included a who's who of future stars, including John Belushi, Dan Aykroyd, Chevy Chase, Jane Curtin, and the late, great Gilda Radner. Radner, in fact, was a standout from the start, beloved by viewers thanks to such unforgettable characters as Roseanne Roseannadanna, teenage nerd Lisa Loopner, and perpetually outraged (but always mistaken) Emily Litella, brought on "Weekend Update" to complain about such hot topics as violins on television, endangered feces, and the deaf penalty. Radner's popularity at the time cannot be overstated. "She combines the physical humor of Lucille Ball with the diverse characters of Lily Tomlin," declared The New York Times in 1979.

Like other members of the cast, Radner went on to have a movie career after exiting the show in 1980. It was while making one of those movies that she met co-star Gene Wilder, famed for his portrayal of Willy Wonka. Wilder would become her husband and, sadly, her widower; Radner died of ovarian cancer in 1989 at the far-too-young age of 42. Here are more tragic details about "Saturday Night Live" original cast member Gilda Radner.

Gilda Radner was just 12 when her father was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor

Growing up in Detroit, Gilda Radner was particularly close to her father, Herman Radner. Not only did she inherit his outsized personality, he also sparked her love of acting by taking her to New York to see Broadways shows. When she was 12, he went to a hospital for some routine tests so that doctors could get to the bottom of strange headaches that had been plaguing him for some time. "They opened him up, found a brain tumor that was too far gone to remove and closed him up again," she wrote in her 1989 memoir, "It's Always Something." The next time she saw him, he'd suffered a stroke; the father that she'd known was gone. "The person disappeared but the shell was still there," she wrote.

Her father spent the next two years at home, severely ill. "I was so young and I think he knew he wasn't going to be around long," she wrote. "Every time he saw me he would become emotional and well up with tears." Herman eventually fell into a coma, with machines keeping his heart beating. "He was in the hospital just barely alive," Gilda recalled. He died six months later.

Gilda Radner felt that she hadn't properly mourned her father's death at the time, and the trauma lingered. "I spent years trying to mourn my father's death properly through psychoanalysis and psychotherapy," she wrote. "It was a very hard thing to understand. I was only a child."

Gilda Radner's mother was also diagnosed with cancer

As Gilda Radner wrote in her 1989 book, "It's Always Something," there was a history of cancer on her mother's side of the family. Her maternal grandmother, in fact, was in her early 60s when she died of stomach cancer, while several other women in her family were diagnosed with the disease.

In 1974, the year before Radner would skyrocket to fame on "Saturday Night Live," her mother received a diagnosis of breast cancer. "It was devastating to my mother," Radner wrote, noting that she underwent a full mastectomy to remove the tumor. A few years after that, a routine checkup revealed that the cancer had returned, and had metastasized to her lung. She endured another surgery, this one to remove part of her lung. Thankfully, that second surgery did the trick, and her cancer didn't return.

Radner herself had a similar scare when she was 18, with her doctor detecting a suspicious lump in her breast. Other doctors were consulted, and she too went under the knife to have the lump removed. "When they wheeled me into surgery, my mother was crying, but I wasn't," she wrote. "I guess I didn't really understand what was happening."

Gilda Radner struggled with an eating disorder as a child

In her 1989 memoir, "It's Always Something," Gilda Radner revealed she'd come to realize that she coped with stress by overeating. That habit extended all the way back to her childhood; when she was just 9 years old, she weighed 160 pounds. Her mother was alarmed enough to bring her to a doctor, who prescribed Dexedrine, a powerful stimulant. There were, however, some severe side effects. "They caused me to have tremendous mood swings and I had to discontinue using them," she wrote.

As a teenager, Radner's fear of being overweight steered her toward numerous crash diets, and she wound up establishing a dangerous pattern that she would carry with her into adulthood. "Any emotion could drive me into binge eating that would be followed by days of rigorous dieting," she explained.

Achieving her dreams of stardom didn't change her issues surrounding her body image. Even when she became the toast of television, Radner was filled with self-loathing. "My picture's in the newspaper, but my body's in the garbage," she wrote in a diary entry, as reported by the New York Post.

Becoming famous caused Gilda Radner's eating disorder to escalate

By the time she soared to fame via "Saturday Night Live," Gilda Radner's bulimia had worsened. In Radner's diaries, obtained by filmmaker Lisa D'Apolito for her documentary, "Love, Gilda," Radner recalled keeping her eating disorder hidden from her cast mates. "I was a total professional about my work, but my private life was all obsessive eating and throwing up," she wrote, via the New York Post. While several of her co-stars were turning to drugs to cope with the pressure of sudden fame, she turned to food. "Like any addiction, the eating disorder took charge and left little time for life," she added

According to "SNL" costume designer Franne Lee, Radner hadn't hid her problem as well as she thought. "I was very aware of her eating disorder. I mean, I knew that every time she ate, she went into the bathroom," Lee said when interviewed for the series "Autopsy: The Last Hours of..."

In 1978, during the "SNL" summer hiatus, she checked herself into a Boston hospital, where she spent two weeks under doctors' care while learning how to embrace a healthier relationship with food. "I weigh 104 pounds and I think I'm fat," she wrote in a diary entry. "I want to learn how to eat normally again — and then perhaps to love normally and accept being loved."

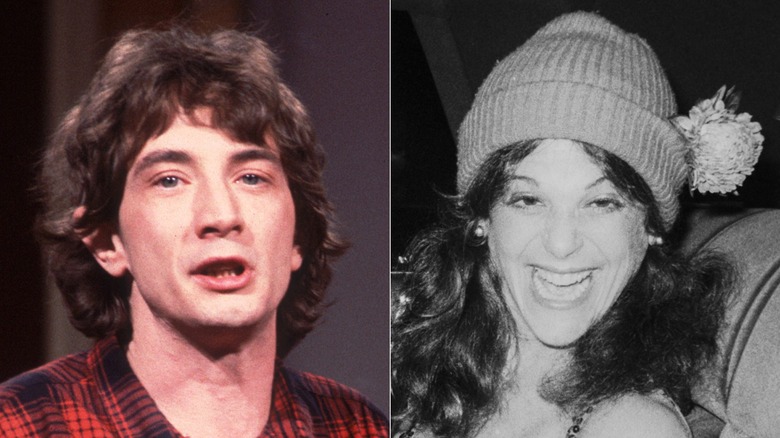

Gilda Radner experienced bouts of depression during her romance with Martin Short

Prior to being cast on "Saturday Night Live," Gilda Radner was a member of the now-legendary Toronto cast of the musical "Godspell," a group of future stars that included Victor Garber, Andrea Martin, and future "Schitt's Creek" star Eugene Levy. In addition, Paul Shaffer — who would go on to spend decades as musical sidekick to David Letterman — served as musical director. Another actor in that cast was Martin Short, whom Radner began dating while they worked together. This was no fling; their relationship lasted for two years until they split up.

While promoting his 2014 memoir, "I Must Say: My Life as a Humble Comedy Legend," Short paid a visit to "The Howard Stern Show" where he discussed his romance with Radner. "She was four years older than I was," Short recalled, detailing the sheer talent and charismatic quality she possessed that made every man she met want to date her, and every woman want to become her best friend. However, he also recalled that she struggled with chronic depression. "I didn't understand how, if you had all these gifts, how you couldn't always be happy," Short explained. "And she wasn't always happy ... I didn't understand."

Ultimately, Short blamed their age difference — she was 26, he was 22 — for his inability to understand why someone bursting with talent wouldn't be constantly happy. "That's a big thing at that age, where you don't know ... at 26, I might have understood women a little more," he mused.

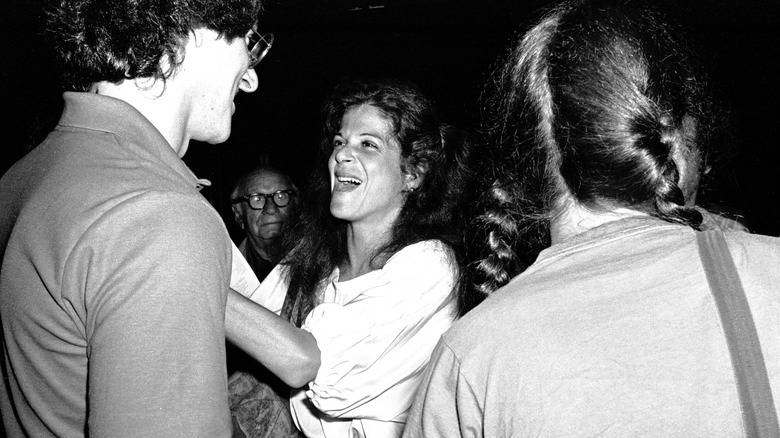

Gilda Radner had a string of failed relationships before marrying an SNL musician

Before she began dating Martin Short, Gilda Radner was in a relationship with Canadian sculptor Jeffrey Rubinoff; she followed him to Toronto, which is where she wounded up being cast in "Godspell." After her relationship with Martin Short came to an end, she dated a lot of men — including many of her co-stars — never finding "the one." She had relationships with Dan Aykroyd, Brian Doyle-Murray, and his brother, future comedy icon Bill Murray. It was for that reason she was reportedly unable to watch "Ghostbusters," which starred both ex-boyfriends Aykroyd and Murray.

In 1980, after a whirlwind romance, she married guitarist G. E. Smith, who played in the "Saturday Day Night Live" band, and also in her one-woman Broadway show, "Gilda Live." "The brilliant musician and the spirited comedienne had a civil ceremony in downtown Manhattan," she wrote in "It's Always Something."

The couple moved into a swanky Manhattan apartment, the Dakota, where their neighbors included John Lennon and Yoko Ono. They were living there, sadly, when Lennon was gunned down by murderer Mark David Chapman that same year. Interestingly, Radner sold that apartment to famed football commentator John Madden, whose heartbreaking death came in 2021.

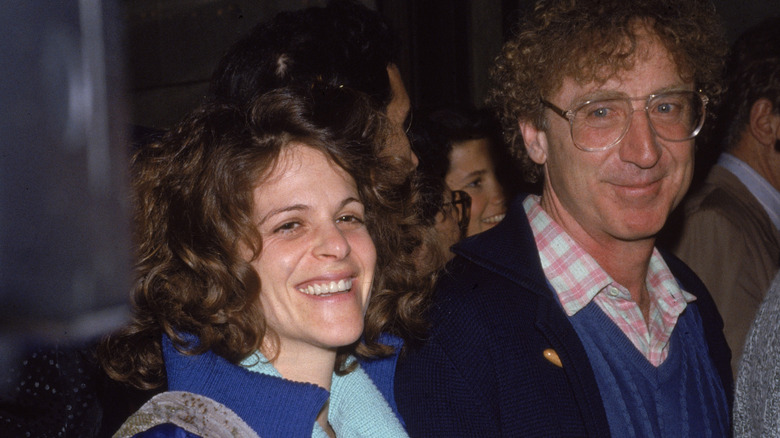

Gilda Radner's marriage to G. E. Smith ended in divorce

Wedded bliss was not in the cards for Gilda Radner and G. E. Smith. Embarking on a movie career, she was cast alongside "Young Frankenstein" star Gene Wilder in the 1982 big-screen comedy "Hanky Panky." Sparks flew between Radner and Wilder, even though he was 13 years her senior. As Radner's friend, Pam Katz, told People (via Time), "There was a chemistry that was palpable, and an electricity in the air. They hadn't been together yet, but there was no chance that they weren't going to be."

Wilder, however, rejected her advances, because he had no intention of having an affair with a married woman. Radner solved that particular problem quite quickly. Her marriage had been rapidly deteriorating, and she and Smith decided to end it, amicably divorcing in 1982. That freed her to pursue a new relationship with Wilder.

The pair moved in together, and in 1984 they flew to France and got married. The settled down in an 18th-century mansion in Connecticut, far from the pressures of showbiz. By all accounts, the two were deliriously happy. "They were constant honeymooners," Joan Ransohoff, Wilder's friend, told Time. "It was fun and infectious to be around them, they were so in love." That happiness, however, would prove to be short-lived when the specter of cancer re-entered her life.

Gilda Radner experienced multiple miscarriages

After tying the knot with Gene Wilder, Gilda Radner was eager to start a family. Sadly, motherhood was something she would never experience. She rejoiced when she discovered she was pregnant, but then had a miscarriage, a pattern that she would experience repeatedly over the years that followed. In her book, Radner wrote about one such experience, while she and Wilder were in London, in the midst of filming their 1986 comedy "Haunted Honeymoon." As she wrote, she woke up one morning to discover she was bleeding profusely. "I was having another miscarriage. It was so soon, only a week after the pregnancy had been confirmed," she wrote.

She recovered from that miscarriage, but felt her energy level to be uncharacteristically low. "I had always had energy — too much energy," she wrote. Just when she started to feel better, she'd once again feel tired. Over time, she began to suspect there was something wrong, and made an appointment with her doctor. She would receive a diagnosis that would, ultimately, change everything.

Gilda Radner's doctor misdiagnosed her serious illness

Concerned about her lack of vim, Radner made an appointment to see her internist. She underwent a complete physical. "I had all my blood work done and chest X-rays and an electrocardiogram — the whole deal. There was nothing wrong with me," Radner wrote in her book.

Stumped, the internist ran a test for the Epstein-Barr virus, which, at the time, was treated with a certain amount of skepticism among the medical community. The test indicated she had elevated antibodies for the virus; however, if that was indeed what ailed her, it was moot because there was no cure. The doctor also suspected what she was experiencing was psychosomatic. "He thought my symptoms might just be from depression," she wrote. The doctor told her that whatever she had wasn't anything worth worrying about, and suggested she take aspirin or Tylenol.

Yet as the weeks passed and turned into months, she began experiencing unexplained pain in her abdomen. She was sent to a gastroenterologist, who likewise couldn't find any cause for the pain. "He thought that my problems were emotional," Radner wrote. "He had heard that my recent movie hadn't done well."

Gilda Radner was diagnosed with stage 4 ovarian cancer

Despite being told she had a clean bill of health, the abdominal pain Gilda Radner experienced did not abate. Finally, a doctor ordered a CT scan to see if that would reveal anything. It did; stage 4 ovarian cancer. She was hospitalized and immediately underwent surgery. "What I didn't know during this time in the hospital was that I didn't have just ovarian cancer," she wrote in her book. "It had spread to my bowel and my liver, but the cells hadn't eaten into those organs. They were just lying on top of those organs, so the doctors had removed all the cancer they could see. The internist told Gene that I had only a 20% chance of survival and that they would not know until I was two months into chemotherapy whether or not I would survive."

After a course of chemotherapy, the news appeared to be positive. Radner was told that her cancer had gone into remission. She shared the joyous news in a 1988 Life magazine cover story, and returned to television with a high-profile guest spot on "It's Garry Shandling's Show." However, her elation at having apparently beaten cancer did not last long.

Gilda Radner's cancer returned a year after she'd gone into remission

With the publication of Gilda Radner's memoir on the horizon, plans were in place for a media blitz, including an eight-city book tour and a sit-down with iconic journalist Barbara Walters. That schedule was ultimately scrapped, with Radner's publicist telling reporters that she'd come down with hepatitis, and was too ill to carry out her promotional duties for the book.

There were whispers that her cancer had returned. Tragically, those rumors were heartbreakingly true. Less than four months after her issue of Life magazines hit the stands, she was sick again. Her cancer was back, and had spread.

In May 1989, Radner was hospitalized at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, where she underwent a CT scan. Three days later, she died in her sleep, with husband Gene Wilder by her side. Two years after her death, Wilder wrote a heartfelt tribute to the late "Saturday Night Live" star that was published in People. According to Wilder, he was blindsided. "Until three weeks before Gilda died, I believed she would make it," he wrote. "Gilda was too strong a fighter. Her spirit would never give in to cancer, I thought. I was wrong."

Gene Wilder believed Gilda Radner didn't have to die

Gene Wilder was devastated by Gilda Radner's death — the life he'd envisioned with her gone. Wilder came to believe the true tragedy of her death was that it could have been prevented; had it been diagnosed earlier, and not missed altogether — particularly given the high occurrence of cancer in her family, her chances of survival would have been far higher.

In his essay for People, Wilder shared that conviction. "The fact is, Gilda didn't have to die," the actor wrote. "But I was ignorant, Gilda was ignorant — the doctors were ignorant." Wilder continued, "She could be alive today if I knew then what I know now." According to Wilder, the cancer could have been caught earlier if doctors had taken two key steps: doing a CA 125 blood test, which would have detected the cancer, and asking about her family history of ovarian cancer. "But they didn't," he wrote. "So Gilda went through the tortures of the damned and at the end, I felt robbed."

Wilder went on to testify before Congress, sharing his experiences with a House subcommittee. "I'm not trying to make up for a wrong that can't be righted," he wrote, explaining that his motivation was to help prevent other women experiencing what Radner did.

If you need help with an eating disorder, or know someone who does, help is available. Visit the National Eating Disorders Association website or contact NEDA's Live Helpline at 1-800-931-2237. You can also receive 24/7 Crisis Support via text (send NEDA to 741-741).