The Untold Truth Of Roe V. Wade

Chances are you've heard of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 United States Supreme Court decision that protects a woman's right to choose to abort a pregnancy. If you haven't, you might be living under a rock. The case is still widely discussed today on both sides of the political aisle, making it one of the most famous Supreme Court cases in history.

Still, while we've all heard of it — especially in response to recent bills that are being introduced and signed into law — there is probably a lot you don't know about the landmark case from more than 40 years ago. For instance, many people refer to Roe v. Wade as the Supreme Court decision that made abortion legal, but that isn't quite accurate.

From the laws that existed before Roe v. Wade and the basis for the case, to the key players (who are Roe and Wade, anyway?) and how the stipulations have changed over time, this is the untold truth of Roe v. Wade.

Legal abortion existed in the United States prior to Roe v. Wade

Saying that Roe v. Wade made abortion legal in the United States ignores the fact that legal abortion existed well before the court case was argued. Essentially until the mid-1800s, abortion was legal until the mother could feel fetal movement (called "quickening"). But in the mid-1800s, the American Medical Association promoted criminalizing abortion and that's the point at which abortion became illegal in most situations.

Then, in the 1960s when Civil Rights protests and the Vietnam War were at their peak, some states began to reform their anti-abortion laws. In fact, when the case first made its way to the Supreme Court in 1971, abortion was legal in six states and Washington, D.C. But despite the fact that abortion was legal in several states, prior to Roe v. Wade, women did not have a constitutional right to an abortion, which meant that each state was able to set its own laws and some had outlawed abortion outright. Others allowed it only in cases when a woman's (or her baby's) life was endangered. Still others allowed for it only in cases of rape or incest.

Roe is a real person, but that isn't her real name

While we often refer to Supreme Court cases in shorthand, the case we're talking about here is actually called Jane Roe, et al. v. Henry Wade, District Attorney of Dallas County. Jane Roe is actually the legal pseudonym for Norma McCorvey, the primary plaintiff in the case. The pseudonym was intended to protect her anonymity and successfully did just that until McCorvey revealed in 1980 that she was the infamous Jane Roe.

When McCorvey was in her early 20s in 1969 and found out she was pregnant for the third time, she decided she wanted an abortion. The problem was that she lived in Texas, one of the states where abortion was still illegal, and she was unable to afford the cost of traveling to another state for a legal abortion. One visit to an attorney led to a referral to another, and it was that second attorney who began the process for the lawsuit that would eventually became a class action suit (hence the "et al." in the lawsuit filing) and make its way all the way to the Supreme Court.

The case was argued more than once

One reason the decision in Roe v. Wade took so long is because the case was argued twice. McCorvey's attorneys filed the lawsuit in 1970 and it was taken up by the Supreme Court in December of 1971. The attorney representing Texas was named Jay Floyd, and he opened his argument by telling what people have since called the "worst joke in legal history," referencing the two female attorneys, Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee, who were representing Roe. He said, "Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the Court. It's an old joke, but when a man argues against two beautiful ladies like this, they are going to have the last word."

Although the case was argued that same day, the law being used for the side of Roe was vague, and Justice Harry Blackmun proposed that the case be reargued. Nearly a year later on Oct. 11, 1972, the case was reargued with a new attorney, Texas Assistant Attorney General Robert C. Flowers, representing the state of Texas. The Court issued its decision on Jan. 22, 1973 — a 7-2 decision that Texas had violated Roe's constitutional right to privacy through its abortion-limiting laws.

It's grounded in the 14th Amendment

While Roe v. Wade had implications for states all across the country, the ruling itself was in response to the Texas law that allowed abortion only in cases of rape, incest, or when the mother's life was in danger.

The Court considered many factors, including attitudes toward abortion, the Hippocratic Oath, common law, English statutory law, American law, and the positions of the American Medical Association, the American Public Health Association, and the American Bar Association. While the Constitution itself does not explicitly mention the right to privacy, the Court recognized such guarantees to privacy in previous rulings.

Ultimately in Roe v. Wade, the Court focused on the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment, which states, "No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws" (via Time). Justice Blackmun wrote in his opinion that this clause also includes a right to privacy for women making a decision about having an abortion.

Proponents claim it is supported in other parts of the Constitution as well

In What Roe v. Wade Should Have Said: The Nation's Top Legal Experts Rewrite America's Most Controversial Decision, legal experts arguing in support of the right to abortion call upon the Equal Protection Clause. They suggest that statutes that limit abortion violate women's liberty and equality because restrictions on abortion compel women to become mothers and, in our society, women bear the brunt of responsibility for childcare. They also note that, due to this disproportionate responsibility, women also face stigma if they decide to give their children up for adoption, suggesting, "Where a woman's life or health is not at risk, the right to abortion is the right to have a reasonable time to decide whether to take on the responsibilities of motherhood."

Taking it a step further, Andrew Koppelman writing for the Northwestern University Law Review in 1990 argues that limiting abortion access essentially leads to forced motherhood and therefore forced labor. This, he says, violates the 13th Amendment, which prohibits involuntary servitude, and he argues this is an even more compelling argument for Roe v. Wade than women's equality or right to privacy.

Roe v. Wade isn't absolute

While the decision in Roe v. Wade said that the Texas statutes — and those like them in other states — that limited abortion access were unconstitutional, the decision did not provide absolute guarantees to abortion. The decision noted that a fetus is not a person, only a "potential life." As such, the decision set up a framework restricting abortion to during times when the fetus is not viable outside of the womb.

In essence, it ruled that, during the first trimester of pregnancy, a woman's right to privacy (and therefore right to an unimpeded abortion) is strongest as the fetus is not a viable life outside of the womb. It is during this time, the ruling stated, that a state may not restrict a woman's right to abortion for any reason. It also stated, however, that during the second trimester, as life becomes more viable, states may only regulate abortion to protect the life of the woman, but, during the third trimester, states are allowed to regulate or prohibit abortion "to promote its interest in the potential life of the fetus" except in cases where continuing the pregnancy would put the woman's life in danger.

Roe v. Wade and strict scrutiny

Based on the Court's trimester framework, it held that abortion in the first two trimesters of pregnancy was a fundamental right. As a fundamental right, the right to abortion was subject to "strict scrutiny," as noted by The Atlantic. This made Roe v. Wade much harder to challenge on a constitutional basis than other laws.

This is because of the levels of scrutiny courts use to determine if the government is violating the Constitution. The lowest level of scrutiny, called "rational bias," means that a government only has to show a "legitimate interest" in an issue to enact a law regulating it. Regulations that pass this test are unlikely to be deemed unconstitutional. "Intermediate scrutiny" is one level higher and states that a government must have an "important interest" in an issue to enact a law regulating it. This means that if a government can't prove the law is actually important, it could be deemed unconstitutional and overturned.

Because Roe v. Wade deemed abortion a fundamental right, this meant that laws challenging abortion needed to pass "strict scrutiny," meaning a government had to prove they had a truly "compelling interest" for challenging the law. This is why Roe v. Wade sat virtually unchallenged for decades.

The decision has faced criticism in the legal community

Despite the 7-2 decision in favor of overturning Texas law and others like it that prohibited abortion, legal scholars like John Hart Ely criticized the ruling.

According to Ely, the Court's decision in Roe v. Wade to protect abortion rights was wrong because it was "not constitutional law and gives almost no sense of an obligation to try to be." Though Ely personally supported legalized abortion, he asserted, "this super-protected right is not inferable from the language of the Constitution, the framers' thinking respecting the specific problem in issue, any general value derivable from the provisions they included, or the nation's governmental structure." Ely also argued that the Court's focus on viability is problematic as defining viability "will become even less clear than it is now as the technology of birth continues to develop."

Even current legal scholars who side with abortion rights have some problems with Roe v. Wade, perhaps most notably Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, as reported by the Chicago Tribune. According to Ginsburg, the decision was too sweeping for the time and was physician-centered rather than "woman-centered," and current cases related to abortion incorrectly focus on "restrictions to access, not expanding the rights of women."

Other rulings modified Roe v. Wade

In the 1992 Supreme Court case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the Court was tasked with deciding whether to overturn Roe v. Wade. Although they upheld the Court's prior ruling, they determined that women retain the right to obtain an abortion, but they also stipulated that a state does have a compelling interest in protecting the life of an unborn child.

The Court ruled in this case that a state can "ban an abortion of a viable fetus under any circumstances except when the health of the mother is at risk." This decision also meant that, moving forward, laws restricting abortion would no longer require strict scrutiny and would instead be evaluated under an undue burden standard. It also eliminated the trimester framework that Roe v. Wade established. Then, in a 5-3 decision in the case of Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt in 2016, the Court further ruled on what constitutes an "undue burden" on women seeking abortions and ruled that any provisions restricting abortions must offer medical benefits sufficient enough to justify the burden it imposes on women to access abortion.

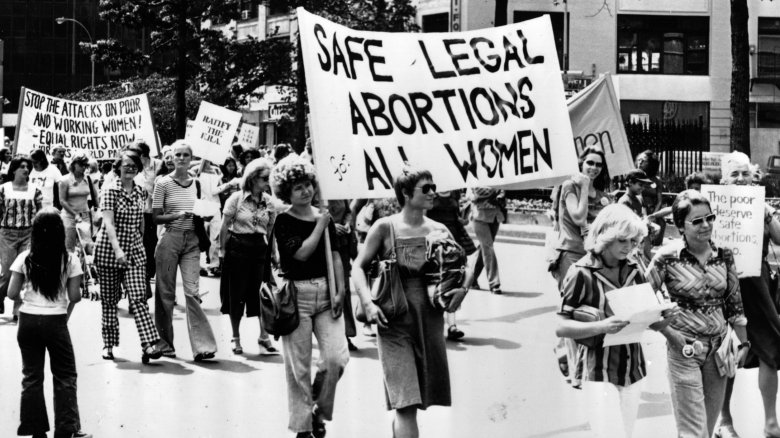

Americans are divided

Just as legal scholars are divided on the Roe v. Wade ruling, so are Americans. In fact, some scholars have argued that the very way Roe v. Wade was written led directly to the divisive nature of the abortion debate today, making it a partisan issue when it historically hadn't been.

Historical trends from Gallup polls also reveal that the percentage of Americans who classify themselves as "pro-choice" versus "pro-life" have overlapped, flipped, and changed dramatically over time, as have opinions about whether (and if so, how) abortion should be legal. The 2009 Gallup poll revealed that more Americans were pro-life than pro-choice for the very first time (since the polls on the topic began). This occurred at the same time that Americans were trending more conservative on many issues, including gun control. But then, according to a 2018 Pew Research Center report, the majority of Americans said abortion should be legal in all or most cases, but the report found a large divide based on political affiliation.

Roe herself was ultimately opposed

Those who are opposed to abortion ultimately included Jane Roe herself, Norma McCorvey. In 1995, while working at a Dallas women's clinic, McCorvey began a friendship with one of the anti-abortion leaders of a group next door, evangelical preacher Reverend Phillip Benham (via CNN). McCorvey quickly converted to Evangelical Christianity, eventually left her lover Connie Gonzales, and blamed the violence at women's clinics on those who were part of the abortion rights camp, saying, "I personally think it's the pro-abortion people who are doing this to collect on their insurance, so they can go out and build bigger and better killing centers."

Initially when McCorvey converted, she spoke to reporters about how she still supported legalized abortion in the first trimester, but, after a few weeks while in the offices of Operation Rescue — the anti-abortion group through which she had begun her friendship with Reverend Benham — she changed her position. Later, she converted again, this time to Roman Catholicism. According to McCorvey, she realized, "All those years I was wrong. Signing that affidavit, I was wrong. Working in an abortion clinic, I was wrong. No more of this first trimester, second trimester, third trimester stuff. Abortion — at any point — was wrong."

She even tried to have the case overturned

McCorvey's newfound pro-life stance on abortion led her to assert in a 1998 interview that, even in extreme cases, abortion is wrong. "If the woman is impregnated by a rapist, it's still a child," she told the Associated Press. "You're not to act as your own God." After converting to Roman Catholicism and leaving Operation Rescue, McCorvey founded her own group called Roe No More Ministry to essentially undo everything she had previously done advocating for abortion rights.

Then, in 2004, McCorvey attempted to have Roe v. Wade overturned by filing a motion in which she asserted she had new information that would affect the case, suggesting that abortions cause women long-term emotional harm, despite the fact that McCorvey never actually had an abortion herself. The court of three federal judges rejected the motion and the case was dismissed. McCorvey passed away at the age of 69 in 2017.

State legislation may challenge Roe v. Wade

In 2019, several states signed bills to ban or restrict abortion. In Ohio, Governor Mike DeWine signed a law that bans abortion as early as six weeks, which the New York Times notes is before many women even realize they are pregnant. DeWine acknowledged that the move was an attempt to make the Supreme Court rule on the law, saying, "So this is exactly what this is, and the United States Supreme Court will ultimately make a decision."

The governor of Georgia then quickly did the same, signing a bill that bans abortion once a fetal heartbeat can be detected — it was the fourth state to sign such a bill into law in 2019, though others were struck down. Then Alabama Governor Kay Ivey signed a bill to make abortion in Alabama a felony. According to AL.com, the bill's sponsors acknowledged that their intent was to "trigger litigation that could lead to a challenge of abortion rights nationally."

With these laws on the books and additional states working to introduce similar bills, the story of Roe v. Wade is far from over.