Surprising Things Hollywood Found Attractive 50 Years Ago

Hollywood found itself in the midst of its own cinematic revolution 50 years ago as the 1960s came to a close. Driven in part by the fall of the Studio System and coupled with the civil rights movement, the popularity of "free love" culture, and the end of the Vietnam War, the late '60s and early '70s in Hollywood gave rise to a generation of unconventional filmmaking. Film critic Tim Dirks described the time for Filmsite.org as showing "tremendous disillusion, a questioning politicized spirit among the public and a lack of faith in institutions — a comment upon the lunacy of war and the dark side of the American Dream."

Hollywood was unapologetic. It was real. And it took the counterculture movement that began in the '60s and went even further with it, focusing less on the feel-good freedom of something like 1965's Beach Blanket Bingo and more on the stark reality of the world it existed in, such as 1969's Easy Rider. So, of course, the Hollywood beauty and fashion trends that came to be popular during the time mirrored these anti-establishment sentiments — at least, for the most part. And some things considered attractive were totally surprising.

The gritty anti-hero type

Take a quick look at the top films from 50 years ago, and you're bound to notice some similarities when it comes to a majority of their male protagonists. Peter Fonda in Easy Rider, Warren Beatty in Bonnie and Clyde, Paul Newman and Robert Redford in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. While the roles and films may differ, the character each actor portrays is arguably a slightly different version of the same man: the rule breaker, the rambler, the charmer.

By the late 1960s, it was no longer the man in the well-tailored suit that filled our screens (and the hearts of women across the country). As The Take described, "These films were centered on complex themes with morally ambiguous messages, reflecting the nonconforming generation disillusioned by Vietnam, upset with the elite and rich with contemplation." And like the films themselves, the men presented as ideal would prove to be morally ambiguous and nonconforming.

Natural, fresh-faced makeup

By the beginning of the 1970s, the women's liberation movement was in full swing. In 1968, women's groups around the country held their first national conference, but privilege and class division kept the movement itself still largely split. In Hollywood, the films of the time reflected the sentimentality of both feminist viewpoints — one demanding change from a place of power and the other not knowing exactly how to assert it.

The 1970 film Wanda — which was written and directed by its star Barbara Loden, who played a working-class woman who flees from her unhappy marriage — is a perfect example of the time. Half a century later, it's regarded as a "feminist masterpiece," both for its candid exploration of raw emotion, as well as its honest portrayal of a woman lost. Loden's look in the film — natural makeup, hair undone — became synonymous with the time.

Elle described the minimal look by saying, "The urge to pare back can be credited to the cultural rise of hippies and anti-Vietnam War feelings, the women's liberation movement (with outspoken leaders who challenged what modern women should look like), and an interest in all that was natural."

Long hair and beards

While women during the late '60s and early '70s were shortening their hair as a part of the women's liberation movement, the opposite was happening for men. As a result of the hippie movement, men were growing their hair out, both on their head as well as on their faces. In Dressing for the Culture Wars: Style and the Politics of Self-Presentation in the 1960s and 1970s, Betty Luther Hillman explained how "others argued that long hair on men represented a more natural version of masculinity."

In 1973's Serpico, Al Pacino's Frank Serpico plays an undercover cop in New York City who exposes corruption in the police force. His look, as well as the plot of the film itself, is indicative of the overall opinion of anti-establishment that many Americans held at the time. The unkempt hair and grown-out beard that Pacino sports in the film became a look that would be seen on the streets for years to come.

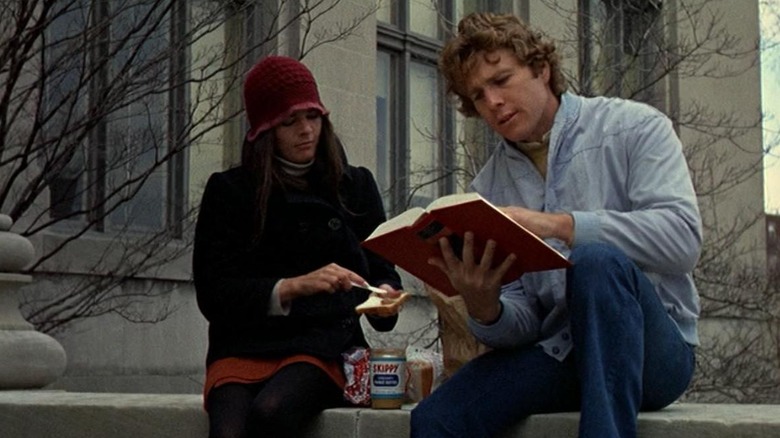

Unisex feathering

Perhaps because the late 1960s and early 1970s were so heavily marked by rebellion — against the government, against sexual norms, and against society itself — the hair of the era would reflect the same sentimentality. Hairstyles were all over the place, representing different cultural and societal influences. Among the most popular styles of the time were the shag, the wedge, and the afro.

Hillman described the role of the feminist movement on hair in her book Dressing for the Culture Wars: Style and the Politics of Self-Presentation in the 1960s and 1970s. Hillman writes, "By failing to look like a traditional woman, this activist challenged the notion that men and women were as different as socially constructed roles of gender made them out to be."

But perhaps the most defining style of the early '70s (which would go on to become the most defining style of the entire decade) began with some wings. Feathered hair was huge, and it wasn't just for women. Ryan O'Neal sported the look in 1970's Love Story, while his real-life love, Farrah Fawcett, would go on to make it the most sought-after hairstyle a few years down the road.

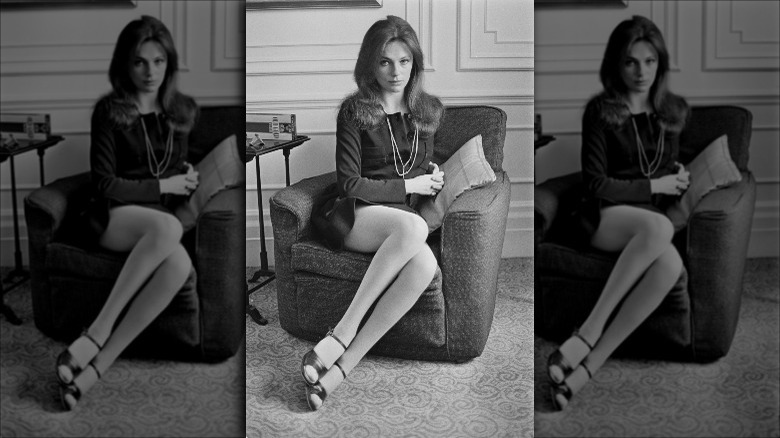

Natural thinness

As the time shifted into the new decade, the appeal of rail-thin frames like '60s fashion icon Twiggy began to fade. Actresses like Barbara Hershey, Catherine Deneuve, and Jacqueline Bisset represented a different kind of body type, one that was thin but still feminine. Hollywood was still largely run by male artists and filmmakers, so the ideal body image presented to women at the time was, of course, curated by the men behind the camera.

In their book The Media and Body Image: If Looks Could Kill, Maggie Wykes and Barry Gunter describe the push for perfection that was thrust on women via media by saying that "in the 1970s publicity images offered women a means of buying the self that men desire just as art had once shown them a male view of themselves."

But thinness came at a price. Psychology Today notes that the 1970s saw an increase in eating disorders, particularly anorexia nervosa.

A different idea of beauty

By the same token, the 1970s saw another kind of body type take center stage. Women like Diane Keaton, who made her big-screen debut in 1970's Lovers and Other Strangers before going on to co-star in 1972's The Godfather, was no 1960s bombshell. Nor was she a waifish Twiggy-esque model. Keaton exuded a kind of "lanky grace," as Bustle put it, that became a signature of the time.

Actress Anjelica Huston, who got her start in 1969's A Walk with Love and Death, was another alternative beauty of the time. She told Vulture in 2019 that when she was cast in 1976's The Last Tycoon, the film's director asked a random woman if Huston was beautiful. Huston shared, "She said, 'I wouldn't say 'beautiful.' Interesting, maybe.' I watched the part fly out the door." But "interesting" would come to mean more than conventional beauty for both actresses, who went on to become Academy Award-winning performers early on in their careers.

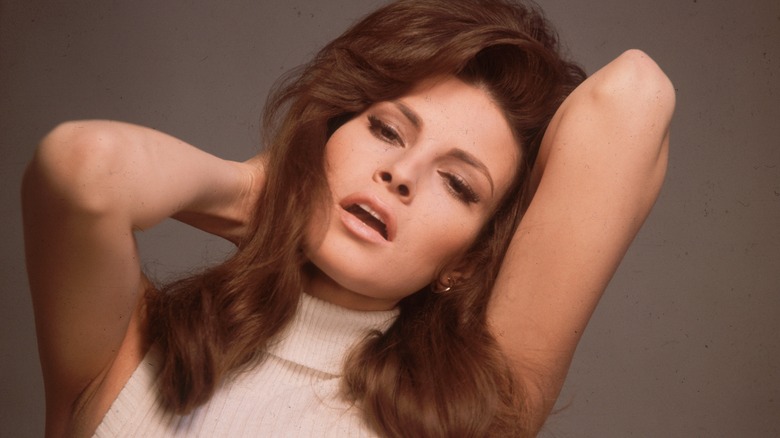

The perfect tan

The "natural" beauty seen on the big screen in the late '60s and early '70s was a true testament to the Hollywood landscape. At the time, Los Angeles itself was famous in its own right as a sort of fairy-tale city stereotype. In her book Pop L.A.: Art and the City in the 1960s, Cécile Whiting lists L.A. stereotypes as "babes, beaches, cars, the strip."

Women in Hollywood perpetuated the tan ideal. From Raquel Welch and Sharon Tate on the big screen to Cher on stage, sun-kissed skin was in. But the 1970s saw the trend shift from a natural glow to a more unnatural bronze. Man-Tan, the first self-tanner, was first introduced in 1959 and opened the door to what would become the booming self-tan industry. The product's main ingredient, dihydroxyacetone (DHA), was approved by the FDA for use in fake tanners in the 1970s (via HuffPost), and it would only take a few years after that for UV tanning beds to gain a foothold.

Counterculture glam

As the country pushed back against societal norms in the late '60s and early '70s, a full-blown counterculture movement formed that would help shape and define fashion. In describing the Counter-Couture: Handmade Fashion in an American Counterculture exhibition at New York's Museum of Arts and Design, Hyperallergic described how fashion in the early '70s reflected evolving sexual attitudes: "Though steeped in protest, the fashions and fads of this era were also frilly and decadent, luxuriant in materials and elaborate in construction."

One need look no further than to David Bowie and his Ziggy Stardust days to see the full extent of counterculture glam. Bowie was the embodiment of the sexual fluidity and outlandishness that would become a hallmark of the 1970s. Time said of his preference to perform as Ziggy Stardust, "Bowie's decision to do so, along with his costumed and highly stylized live show, offered a total rebuke to the naturalist approach of the previous hippie era."

Masculine tailoring

The feminist wave of the early '70s brought with it a rebellion against what was considered to be "proper" women's fashion. A 1977 New York Times article called "Feminism's Effect on Fashion" notes how the women's movement gave women "the courage to express their individuality." No longer would they be forced to wear uncomfortable skirts and undergarments because society told them to. It was about wearing whatever they wanted.

Sometimes referred to as the "anti-fashion" era, women's clothing in the early '70s was less about what looked good and more about what felt good, and Hollywood reflected as much.

With this change in clothing standards, women began to embrace donning men's fashion. Actress Diane Keaton has always been known for her gender-bending suit style, but she wasn't the only one that helped popularize this trend. Years before Keaton's Annie Hall hit the big screen, there was 1972's What's Up, Doc?, a comedy starring Barbra Streisand and Ryan O'Neal. The film's costuming took tailoring to another level, as Streisand's fitted pantsuits managed to seamlessly blend a masculine suit style with a feminine silhouette.

The collegiate look

Ali MacGraw became an overnight sensation in Hollywood after starring in her first two films, 1969's Goodbye, Columbus and 1970's Love Story. The actress was 30 years old and playing a college student, but audiences were captivated by her. Sheila Weller wrote for Vanity Fair that Love Story was responsible for ushering in the "Era of Feelings" in the 1970s, saying that "it snapped the twig of popular culture." Weller explained, "Instantly gone was the hard-rock-fueled sexual revolution; in its place were soaring strings, tragic love, and sweetness."

The iconic movie is also largely credited with creating one of the most iconic style trends of the decade: the collegiate look. MacGraw's Love Story character, Jennifer Cavalleri, was an Ivy League girl, and she dressed the part. Turtleneck sweaters, striped scarves, and beanies became the look for college-aged girls. And the impact of the film on the fashion world can be seen throughout the work of designers Ralph Lauren, Tommy Hilfiger, and Marc Jacobs.

The dropout type

The 1970s "New Hollywood" style of filmmaking was a direct reflection of the social unrest that marked the beginning of the decade. The New York Times said of the era, "By the early 1960s the old studio system was in shambles, run by old men who, out of touch with the times-they-are-a-changin', were churning out pricey duds like Cleopatra to shrinking, indifferent audiences." The new generation of filmmakers took interest in making movies for younger audiences, inspired less by box office draw and more by European cinema and real-life experience.

The people portrayed in these films were representative of that "New Hollywood" audience. Characters like Dustin Hoffman's Ben Braddock in The Graduate and Jack Nicholson's Bobby Dupea in Five Easy Pieces showed on the big screen what Americans were feeling in their everyday lives: unrest and a general lack of direction. Dupea's arc, described by The New York Times as having "walked away from his art-bourgeois family to drift unhappily among the working classes ... for whom he largely shows contempt," became a familiar replacement for the stories of heroes (think John Wayne) of Old Hollywood.

Prints on prints on prints

Experimentation in fashion became increasingly popular in the 1970s. In 1971, The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour premiered, which gave audiences a weekly glimpse into Cher's extravagant closet. The singer, who would go on to become an Academy Award-winning actress, was known for her willingness to try anything and everything in fashion at least once. Marie Claire listed her entire '70s wardrobe as one of the decade's style-defining moments, and Vogue said her "penchant for pushing boundaries was nothing short of era-defining in the '60s and '70s."

Music and fashion excess were seen all over television in the early '70s. The Osmonds, a family group that had gained popularity in the '60s, blew up as teen idols and so did their fashion choices. Enter matching jumpsuits, a trend the family has another entertainment idol for whom to thank. Wayne Osmond told the Las Vegas Review-Journal that it was music icon Elvis Presley who suggested the idea. "He told us, 'I got a new look for you," Wayne recalled. "He thought we should wear jumpsuits like his."

Fitted silhouettes and natural flow

By the early 1970s, the United States was experiencing an economic downturn. The political focus of the 1960s had shifted into spirituality and, as Brenda Polan and Roger Tredre describe in their book The Great Fashion Designers, "drug-fueled altruism." Fashion became simplified and romantic, "taking inspiration from other times and other places."

In 1968, designer Halston opened his first salon in New York City. Vanity Fair said his fashion message was clear: "Clean, elegant, simple, and spare. Luxurious and rich." He soon became a favorite among the Hollywood elite like Bianca Jagger and Liza Minnelli, and, by 1973, Halston was known as the "golden boy of fashion." His minimal designs were known for the way they flattered a woman's body, regardless of body type. And although he would routinely use stick-thin models in his shows, according to Polan and Tredre, Halston was proud of being able to dress "Miss Average America."

There are no rules

More than anything, the time between the late '60s and early '70s came to be known for rule-breaking and the redefining of fashion and appearance. In the early '70s, Vogue announced, "There are no rules in the fashion game now," as Jacqueline Herald noted in her book Fashions of a Decade. Herald also describes the transition from couture to ready-to-wear by saying design houses like Christian Dior and Yves Saint Laurent were now "catering to the more casual and practical moods of the moment."

Comfortable and chic clothing was everywhere in Hollywood, including, of course, on the big screen. Even films like 1972's The Godfather portrayed expensive style as something the average woman could be seen wearing. Jane Fonda in 1971's Klute exemplified the rule-breaking style that was seen as attractive 50 years ago. From the shag hair to the flared pants, miniskirts, knee-high boots, and fringe, Fonda's character Bree Daniels was everything that would come to define the beginning part of the decade.