Surprising Things Men Found Attractive 50 Years Ago

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Fifty years doesn't seem like a very long time in the vast scheme of things, but it's enough time for things to have drastically changed. The differences between the late 1960s/early 1970s and today go beyond the obvious, such as the astonishing technological advances that have been made since then. Beauty standards were also shockingly different, reflecting the turbulence of the era. Here are some of the most surprising things that men found attractive 50 years ago.

Lighter skin

Racism was rampant in the 1960s, although the Civil Rights Movement helped to create significant change by the end of the decade. Anti-miscegenation laws, which had prevented people in several states from marrying those of another race, were struck down in 1967. In spite of the reforms made in the 1960s, racial prejudice was still prevalent. By the 1960s, the Miss America Pageant still didn't allow African-American contestants. In 1968, a Miss Black America Pageant was held on the same day as the Miss America Pageant in response to the organization's discrimination. It would be another two years before an African-American woman, Cheryl Browne, won a state title in the Miss America Pageant competition.

Even within the African-American community, a preference for lighter skin was apparent, although this slowly began to change in the 1960s with people embracing their skin color. Things are a little better today, but there is still discrimination against those with darker skin. A 2016 Time article said even in modern times "dark skin is demonized and light skin wins the prize" because of the "deeply entrenched racism" of the United States.

Rail-thin bodies

For a time, it looked like fuller figures would be, if not the dominant ideal of beauty, at least an accepted standard. In the 1950s and early 1960s, voluptuous women like Marilyn Monroe were cultural icons. Still, "there was also a significant move toward slimness," wrote Sarah Grogan in Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children. As the decade progressed, the slim trend became more pronounced, becoming "particularly acute... when the fashion model Twiggy became the role model for a generation of young women." As time went on, "models became thinner and thinner," wrote Grogan.

Flat chests

As models became thinner, curves became less desirable. It was in the late 1960s when the obsession with eliminating cellulite began. Linda Przybyszewski wrote in The Lost Art of Dress: The Women Who Once Made America Stylish that at this time "curvaceous women were passed over in favor of underweight teenagers."

The desire to be thin led to a preoccupation with weight, especially among younger girls. "Before the 1920s, teenagers worried about becoming better people," wrote Przybyszewski. By the 1960s, however, "weight loss became the primary obsession."

Flat butts

The desire for flatter chests correlated with an obsession for smaller butts. Przybyszewski wrote that the fear of cellulite caused women to do anything they could to eliminate "what they identified as water, wastes, and fat trapped inside women's hips and thighs." One woman who was written about in Vogue magazine in the late 1960s "managed to reduced her 39-inch hips down to 34 inches through exercise, 'standing correctly,' and using 'a special rolling pin.'" Such regimens were typical in the late 1960s. "If you didn't want to rub your butt yourself," wrote Przybyszewski, "you hired a masseuse to do it for you."

The desire for more boyish figures was not entirely to please men or to conform to fashion. Battleground: The Media, edited by Robin Andersen and Jonathan Alan Gray, noted that "the changing shape of women's bodies has in many ways served to reflect larger cultural values." Throughout history, "a thin, straight figure was prized" at times "when women were striving to demonstrate their equality."

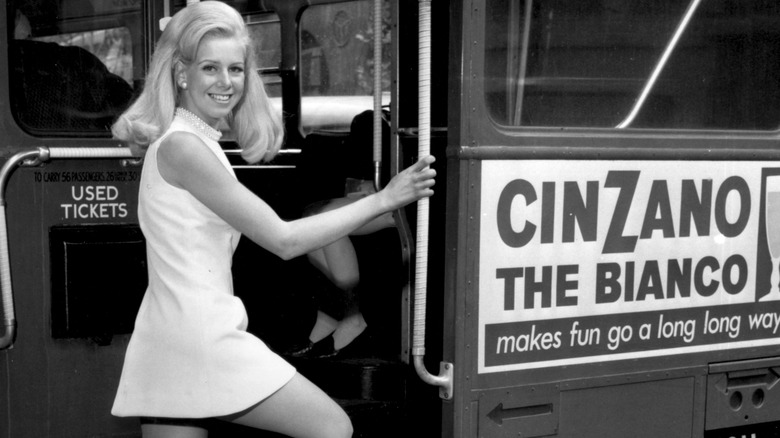

Exposed legs

In Fashion: A History from the 18th to the 20th Century, Akiko Fukai wrote that "the young found that displaying their physique was the most effective means of setting themselves apart from the older generation." The miniskirt came into vogue as "bare legs... developed through various conceptual stages in the 1960s."

As hemlines rose, more attention was paid to the length and shape of a woman's legs. In Women of the 1960s: More Than Mini Skirts, Pills and Pop Music, author Sheila Hardy wrote that many women felt they "did not have the legs for a miniskirt." The emphasis 1960s fashion placed on women's legs also influenced shoe styles. Tall, pointed boots came into fashion, off-setting the short skirts of the era.

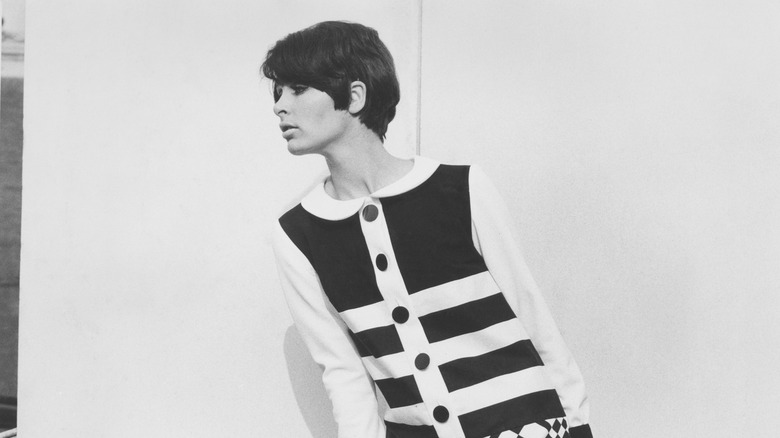

Androgyny

Coinciding with the preference for more boyish figures was the rise of unisex clothing and androgynous styles. This echoed a similar trend from the 1920s, when "androgyny [began to be] associated with the search for greater independence for women," wrote Rebecca Arnold in Fashion, Desire and Anxiety: Image and Morality in the 20th Century. Arnold wrote that the rise of androgyny in the 1960s helped to "denote freedoms gained and the rejection of a preceding claustrophobic femininity."

Perhaps even more interesting is that this inclination towards androgyny was also adopted by men. PBS noted that "for a brief time, mostly in 1968, unisex was everywhere, and with it came a fair amount of confusion in the media." The piece went on to quote Everett Mattlin, who, in 1968, wrote in the Chicago Tribune that "the whole male-female relationship is confused." Traditional gender roles were beginning to evolve at this time, which Mattlin believed could lead to a "healthier climate."

The Lolita look

The suppression of women's curves led to the popularity of what Imagine Nation: The American Counterculture of the 1960's and 70's, edited by Peter Braunstein and Michael William Doyle, called a "prepubescent look." Lithe, young-looking Lolita types like Twiggy dominated the fashion world. This "look of exaggerated youthfulness expressed the associated sensibility that maturity, in dress or behavior, was a dirty word, a sign of premature death, and therefore something to be warded off as long as possible."

According to The Mancunion, the 1960s have today "become a symbol for the social conflict between the old and the new." The "Lolita look" embodied the spirit of the era, representing youth and vigor.

Going braless

The rebellion against traditional gender norms was also evidenced in women's undergarments. By the late 1960s, many women were going braless as "a political, protest move symbolizing freedom and rejection of traditional views of femininity," wrote The Lala.

Fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent contributed to making going braless not just a form of protest but also a fashion trend. His sheer designs were always modeled by women who wore no undergarments beneath them. This, too, was a political statement. Dazed wrote that "the decision was less about pleasing the onlooker, and more about asserting equality between the sexes."

Long, straight hair

The time period was noted for a departure from formality and tradition. In Fresh Lipstick: Redressing Fashion and Feminism, Linda M. Scott wrote that there was a "preference for long, straight hair" in the late 1960s. Many men also wore their hair long at this time. The changing hairstyles weren't just about following fashion. For many, they were also "acts of rebellion against the highly constructed female hairdos and very short male haircuts of the previous generation."

Subservience

The 1960s might have been a time of change, but ads from the era show that women were still expected to be homemakers and sex objects. In spite of the great strides made towards gender and racial equality, women still did not have the same rights as men. Even by the end of the decade, it was legal for a bank to deny an unmarried woman a credit card — married women were often required to have their husbands co-sign. Some states still banned women from serving on juries.

When it came to higher education, attending an Ivy League school was incredibly rare for women in this decade. The University of Pennsylvania and Cornell both allowed women to attend as of the 1870s, but only in special circumstances. Yale and Princeton didn't start accepting women until 1969, while Harvard, Brown, and Dartmouth held out until the 1970s. Columbia didn't offer admission to women until 1981.

In The Feminine Mystique, published in 1963, Betty Friedan summed up the frustration of the generation, writing, "A woman today has been made to feel freakish and alone and guilty if, simply, she wants to be more than her husband's wife."

Sobriety

A lot of people envision the 1960s as a decade long booze-fest where day drinking (especially at work) was the norm. While this is partially true, it was far more acceptable for men to indulge in multiple alcoholic beverages each day than women. More and more women were moving away from conventional gender stereotypes, but women who drank frequently were seen as decidedly unfeminine. A glass of wine with dinner or a cocktail on the weekend was acceptable, but getting drunk was not.

Warning women not to drink too much was not just a societal pressure, but one that was backed up by public service announcements of the day as well as the mainstream media. "People think of the woman drunk as an old hag," warned the Saturday Evening Post in 1962. "Among men, heavy drinking is often taken as a sign of virility, and the phrase, 'Drunk as a lord,' is a tribute. No one ever said approvingly, 'She was drunk as a lady.'" That sentiment still remained true by the end of the decade.

Smoking

Drinking in excess may have been taboo for women looking to attract a man, but smoking was considered attractive. While a link between smoking and lung cancer had been established years before, the practice was still widespread. In 1964, the surgeon general warned that "cigarette smoking is a health hazard of sufficient importance in the United States to warrant appropriate remedial action."

In spite of such warnings, smoking was largely considered to be glamorous and sophisticated. The tobacco industry targeted women in the 1960s, taking advantage of the growing feminist movement by portraying smoking as the pinnacle of gender equality. Virginia Slims were launched as a women's cigarette in 1968, with the slogan "You've come a long way baby!" Other cigarette ads from the late 1960s show young, attractive women partaking in what is shown as an elegant pastime, conveying the message that women who smoked were refined and sexy.

Unemployment

By the late 1960s, more women were working than ever. While they were making great economic strides, working women faced a certain stigma. It was far more acceptable for single women to work than married women, as a woman's primary duty was still expected to be to her family. In 1967, just 44 percent of married American couples lived in dual income households, compared to more than half of married couples today. Working wives and mothers were thought to destabilize home life and their families.

History professor Stephanie Coontz told the Harvard Business Review that middle-class women were the most stigmatized, and that if they did choose to enter the workforce they were expected to wait until their children had grown. "And these women — it is hard for modern people to understand just how insecure, how depressed, how a low the self-esteem was of these stay-at-home moms in those days," she said.

Leg makeup

The rise of the miniskirt meant that women felt the pressure to put their best leg forward. By the mid 1960s, a new trend was emerging: leg makeup. Makeup had been used on legs before, perhaps most notably during World War II when a shortage of stockings propelled women to draw on stocking seams with eyeliner to make it look like their legs weren't bare. The leg makeup of the 1960s, however, was primarily used to cover up flaws that were now exposed thanks to the shorter hemlines of the era. Women would carefully apply makeup to their legs to cover up blemishes before putting on hosiery. Bruises, scars, and other imperfections were covered up with cosmetics, and then further concealed with stockings.

The use of leg makeup shows just how conflicted women in this era were. The women's liberation movement was empowering females, and women were beginning to embrace their bodies, but many of them still felt the pressure to conform to society's beauty standards.

Athletic skills

Athletic women were "in" at the end of the 1960s, but not for the reason that you might think. Athletics were viewed as a way for women to maintain "attractive" figures. Women became more active in sports in the 1960s, especially in high schools and colleges, although women's sports were not considered to be on par with men's sports.

A woman with an athletic physique was considered attractive, but female athletes had a long way to go to be accepted in society. It wasn't until 1972 that the U.S. Congress passed Title IX, which helped secure funding for women's sports. The first female athlete to appear on the cover of Sports Illustrated, Jackie Joyner-Kersee, didn't do so until 1987. While female athletes today are considered strong and capable role models, the female athletes of the 1960s were largely viewed as hobbyists whose pastimes were only indulged in order to help them remain slim.

Dyed hair started to become more acceptable 50 years ago

Hair dye was not always considered to be entirely acceptable, but that started to change half a century ago. Part of the stigma was because dying hair was thought of as "vain" and "not respectable," noted CNN, but also because of safety concerns surrounding the chemicals used to color hair.

As the decades passed, the introduction of home dyes made dyed hair more common and, by the 1970s, nearly half the women in America were reaching for the dye. According to the book Gidgets and Women Warriors: Perspectives of Women in the 1950s and 1960s, hair dye company Clairol marketed blonde hair as attractive and desirable starting in the 1950s, pushing the color with ads oozing sex appeal — Clairol even brought us the phrase "blondes have more fun." It's no surprise, then, that by the time the 1970s rolled around, many were opting to go blonde.

Many of the most admired women of the era like Farrah Fawcett rocked blonde strands, observed Glamour. Other notable blondes of the time include Debbie Harry, Olivia Newton-John, Meryl Streep, Peggy Lipton, and Joni Mitchell.

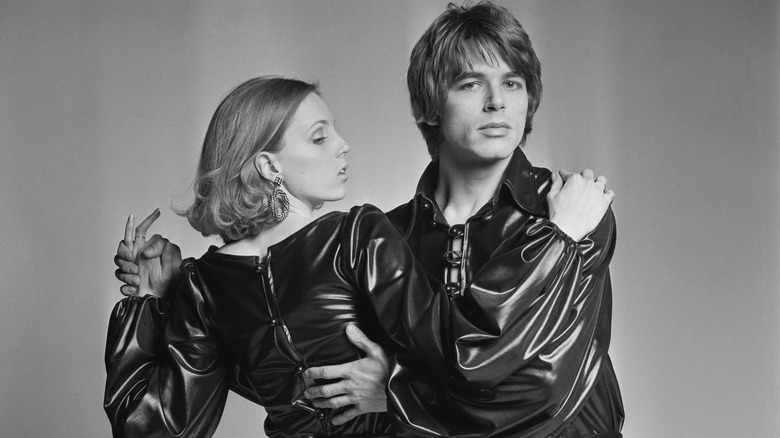

Feathered hair was a hit 50 years ago

Farrah Fawcett's blonde hair was always styled in a feathered cut in the 1970s, a look that Redbook wrote "essentially defined beauty in the 1970s." Even 50 years later, when many people think of the era they think of Fawcett's iconic look which, as noted by Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History, was created by hair stylist Allen Edwards.

Women looking to imitate Fawcett's lusted-after locks weren't the only ones to adopt this hairstyle, though. Many men also wore feathered hairstyles in an example of the androgynous look that was considered particularly attractive in that era.

While maintaining the soft curls of a feathered hairstyle could be a lot of work for those who weren't blessed with wavy hair, the look wasn't meant to look artificial. Instead, it was part of the time period's commitment to what the book The Art of Makeup called a "no fuss, fresh, all natural look."

Many women opted for a natural makeup look 50 years ago

The natural look of 50 years ago wasn't isolated to hairstyles. A fresh face was also considered to be particularly appealing, noted The Art of Makeup. Natural didn't mean going about with a bare face, though, and women put a lot of effort into getting the perfect, sun-kissed glow. Fake-tanning was popular, and, while most women skipped foundation, they would use bronzer for that bit of shimmer. Makeup colors tended to be more about enhancing the natural color of one's features rather than making them pop, with "pearlescent colors" dominating the color palette.

The push towards a more natural look was primarily due to social issues, so women sporting the style would have been particularly attractive to activists of the day. Per Elle, "the urge to pare back can be credited to the cultural rise of hippies and anti-Vietnam War feelings, the women's liberation movement ... and an interest in all that was natural." There was also a growing awareness of the dangers of pollution, which meant that "cosmetics were at odds with the earthy beauty ideal being celebrated."

Big lips were attractive 50 years ago

Lips have mesmerized men since time immemorial, and many men 50 years ago found large ones to be particularly appealing. Their attraction to big lips wasn't just driven by the fashion of the era — The Cut noted that it was basic biology as "full lips signal both youth and vitality."

The yen for pouty lips was nothing new 50 years ago, but it was a change from the dominant lip look of the 1950s, which placed more importance on having a fuller lower lip. The following decade saw more emphasis on large lips, and advancing technology led to some people seeking out some pretty scary methods to achieve the look. In the 1960s, silicone was briefly used as a lip filler but wasn't entirely safe, noted Dazed. By the 1970s, silicone was out and some doctors instead used bovine collagen to give people larger lips.

Per Slate, sex symbols of the day embodied the big-lipped ideal, with Bianca Pérez-Mora Macias, who was married to Mick Jagger in the 1970s, being the reigning queen.

Thin eyebrows were all the rage 50 years ago

Women looking to catch a man's eye 50 years ago were likely to take the tweezers to their eyebrows. That's because thin eyebrows were very much in back then. Thin eyebrows weren't just a beauty standard 50 years ago, though. The reigning eyebrow look that decade was actually a vintage style that called to mind the dainty eyebrows of the 1920s and the 1930s. The book Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History noted that thin eyebrows first came in vogue in the 20th century along with the rise of the film industry, as they were more visible on camera.

While fashion-forward women of the 1940s and 1950s tended to prefer a bolder eyebrow, the 1960s ushered in an era of experimentation in which some people went so far as to shave off their eyebrows and draw them back on with a brow pencil. By the 1970s, thin was back in, and stars like Donna Summer, Diana Ross, Pam Grier, and Aretha Franklin rocked the thin brows that decade.

Working women tended to follow more traditional career paths 50 years ago

There was a definite hierarchy in the work force 50 years ago. Magazines from the time, noted Flashbak, were brimming with job ads for women, but they were typically "for low-wage, low-skill positions." Being a pilot was considered a man's career, but women could serve passengers on a plane as a stewardess — "Airlines need women!" read one ad from the time. Modeling, nursing, and secretarial work were also careers that typically recruited women, and women in such ads were often young and conventionally attractive.

While women could enter other fields, very few did. Statistics from the American Medical Association's Physician Masterfile (via Pinnacle Health Group) show that out of the 334,028 physicians in the U.S. in 1970, just 25,401 were women, while Law Crossing noted that women made up just 4 percent of legal practitioners.

This was largely because women were still expected to focus on raising a family. As economist Janet Yellen wrote in an essay for Brookings, "most women still expected to have short careers, and women were still largely viewed as secondary earners whose husbands' careers came first." Women who prioritized a career, then, often did not appeal to traditional-minded men.